I've just returned home after a long trip to Manhattan. It was the big finale for a project I've been working on for months which involved working crazy hours trapped in the horrible neon hell that is Times Square. I was keen to try and shoot some stuff whilst there, but noticed a conspicuous absence of tripods from the square itself. A quick web search revealed a mix of people saying it was fine and others saying that they had got tickets for trying it without a permit. I had lugged my Deardorff all the way, but figured I had too much to loss by pushing my luck. I did manage to take a group shot of the project team. Having carried the film through 2 x-ray machines and loaded it in a not-so-dark room, I have no idea whether it will come out. Watch this space for details...

On the final day of the trip, I managed to sneak over to the International Centre of Photography. The ICP currently has 3 exhibitions. The first, Remembering 9/11, was a multi part exploration of memories and healing. The stand out element for me was a selection of photos taken by Francesc Torres (Memory Remains: 9/11 Artifacts at Hangar 17). This section covered items which have been recovered from the ruins of the World Trade Centre. I found it incredibly moving and was stunned by the artists ability to mix scales between the very large and the very small with intense effect.

As part of the same exhibition a video installation showed an artist clearing their studio from debris which had blown in by the destruction of the towers. I have never been able to get my head around video installations in the past, and I'm afraid to say that this one was no exception. My criticism remains the same; with no evidence of any technical skill or understanding of narrative the only thing going for this piece was its choice of subject. Any other medium would have done more justice to this topic than the horrible monotonous drone of amateurish imagery. I guess I works for some people, but for me it was terrible.

Other exhibitions included a selection of work by Peter Sakaer. This was an excellent collection of photo journalism from the depression era. Most of it appeared to be contact silver gelatin prints and the quality was excellent. The sharpness and tone were breath taking and it had the effect of bringing the human life depicted in the pictures right into the modern age. Sakaer's work has a very graphic feel and his mix of people and store fronts has a haunting vibe. I would highly recommend this exhibition.

Whilst in the ICA I picked up copies of Ansel Adam's celebrated technical manuals; The Camera, The Negative, and The Print. I'm working my way through the first volume at the moment. It's ace!

I'v been working my way through some of he course exercises this week. I'll post my results shortly.

Wednesday, 23 November 2011

Sunday, 6 November 2011

AoP: Exercise 3 - Focus at different apertures

Exercise 3 asked us to shoot the same scene using a range of different aperture settings.

Again I used the collection of 3 film cameras and focused on the press camera in the middle. I then took 3 exposures with decreasing aperture size.

Again I used the collection of 3 film cameras and focused on the press camera in the middle. I then took 3 exposures with decreasing aperture size.

|

| f/5.6 |

|

| f/11 |

|

| f/22 |

I was shooting in my living room and was keen to avoid the harsh overhead lights, or the camera's onboard flash. With these considerations I was already shooting on fairly long exposures whilst wide open. The small aperture required for some of these shots meant long exposures (25 seconds in the last shot).

Conclusion:

Everything else being equal, depth of field increases as the aperture decreases in size. With the aperture wide open we can use the shallow depth of field to draw attention to our plane of focus. With the lens stopped down, more of the picture becomes sharp. Whilst the limits of acceptable focus are fairly subjective, it cannot be denied that the in focus area is increasing in depth as we progress through the 3 images.

Looking at hard copies of the images I noticed another effect; the in-focus areas of the f/11 image look sharper than the in-focus areas of the f/22 image (although more of the f/22 image is in focus). There are lots of possible explanations I can think of for this:

1) A comparative effect. With something softer to compare it to we might perceive the sharp bits of the picture to be particularly sharp.

2) A diffraction effect. When the lens is stopped down a lot the lens starts to behave like a pinhole and light rays will become diffracted as they pass through the small aperture. This could produce an overall softening of the f/22 image.

3) Camera wobble. The f/22 image required a very long exposure time to compensate for the low amount of light that was being transmitted through the small aperture. Camera wobble over the duration of the shot could have caused the shot to soften.

My shot notes for this exercise can be seen below:

AoP: Exercise 2 - Focus with a set aperture

Exercise 2:

In this exercise we were asked to fix the cameras aperture as wide as possible and take a series of pictures focused at each of foreground, mid-ground and background. I lined up 3 old cameras and used a tripod to mount an NEX-5 pointing down the length of them. I used the longest zoom possible (55mm) to maximise the depth of field effects and then shot the following 3 pictures:

Conclusion:

In this exercise we were asked to fix the cameras aperture as wide as possible and take a series of pictures focused at each of foreground, mid-ground and background. I lined up 3 old cameras and used a tripod to mount an NEX-5 pointing down the length of them. I used the longest zoom possible (55mm) to maximise the depth of field effects and then shot the following 3 pictures:

|

| focused on Rolleiflex (closest camera) |

|

| Focused on Press camera (middle camera) |

|

| Focused on Deardorff (furthest camera) |

By using the widest aperture available on this lens, combined with a long zoom and a relatively close camera to subject distance, we were able to use selective focus and shallow depth of field to draw attention to the area of the picture in sharpest focus.

It is worth noting that the amount of blur in the out of focus area varies with the focus point in the picture. the closer the lens is focused, the greater the bokeh in the de-focused areas. To make this explicit; notice how the Deardorff seen when focused on the Rollei appears more blurred than the Rollei does when focused on the Deardorff...

The exercise asks us to choose a favourite and justify it.

Of the 3 shots, the first shot with the closest focus demonstrates selective focus the most. Since the cameras are arranged with increasing age as we move further away from the camera (70's, 50's, 40's) and also increasing size (120 roll film, 5"x4" sheet, 10"x8" sheet), the increasing blur seems to re-enforce this progression

My shot notes for this exercise can be seen here:

AoP: Exercise 1 - Focal Length and Angle of View

Exercise 1 asked us to shoot a scene using:

1) A natural zoom - something that closely matches our day to day perception of the world.

2) A wide zoom - the angle of view which encompasses the maximum amount of scene.

3) A long zoom - an angle of view which blows up detail and shows close-up detail.

|

| 1) 35mm zoom |

|

| 2)18mm zoom |

|

| 3) 55mm zoom |

All 3 shots were taken without moving the camera.

I then uploaded the shots to an iPad and offered them up against the scene whilst standing in the original camera position and tried to match the image into the scene.

1) The natural shot needed to be held at an intermediate position.

2) The wide shot needed to be held very close.

3) The long shot needed to be held at arms length.

Conclusion:

Changing the zoom factors of a zoom lens, or changing between prime lenses of different lengths is comparable to viewing a scene through different sized windows. The perspective and alignment of objects within the scene is unaltered by the choice of lens, but the field of view is.

My shot notes detailing exposure and zoom settings can be seen below:

Sunday 6th November

I’ve just got my hands on the course material for The Art of Photography (henceforth AoP) and have started making some progress through it. The course material seems well put together and looks like it is suitable for a wide range of levels of background experience. My own background is very technical and my hope is that I can use this knowledge as a tool to explore some aesthetic elements of photography.

Having read through the introduction, our first few projects appear to tackle some of the fundamentals of camera technique which are of critical importance to image making. I’d say that I’m already comfortable with the techniques covered in the introduction, but I’m keen to attempt the shots requested in the exercise for fear that over confidence will cause problems when I start moving outside of my comfort zone.

Over the past few years, I’ve spent lots of time thinking about the mechanics of photography and optics and have found a beautiful overlap between the geometry of my maths background and the questions I started asking about the processes of using lenses and cameras. I think a good start to my learning log / blog might be to start formalising and recording the thought experiments that make up my knowledge of optics. My approach is initially quite technical and makes sense to my overtly logical outlook. I haven’t seen camera optics described in this way and I’m interested to know if others find them illuminating (no pun intended). I hope these will complement the exercises in the course and will also form a starting point for some of the more technical posts I’m thinking about for the upcoming assignments.

Part 1 - An idealized camera

In reality, a modern camera is a complicated beast. Even ignoring the intricacies of a digital sensor, the optics of an entry level digital SLR alone serve to obfuscate the fundamental purpose of a lens and camera. At its most elementary level, a camera is a machine used to capture the light from a real world scene at a given moment in time and render it onto a 2 dimensional plane with some degree of permanence. As we begin to explore the workings of such a machine let us start by considering an idealized version of a camera and examining what information we can deduce.

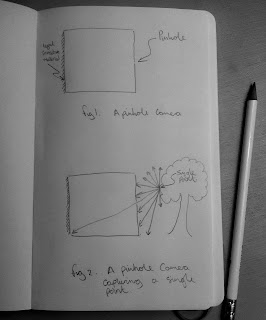

A pinhole camera can give us a tremendous insight into the behaviour of light and light capturing devices. In essence, a pinhole camera consists of a sealed box with a tiny hole on one face and a light sensitive element on the adjacent inner face; either a piece of film or a digital sensor. Figure 1 shows just such a device.

Let us now consider the operation of a pinhole camera. Figure 2 shows the camera placed near a tree. If we consider a single point on the tree then we can imagine light from the sun and surrounding environment hitting this point and the point responding by bouncing light back in every possible direction. Only the ray which intersects the pin hole is allowed to enter the camera, and it’s illumination of the light sensitive material is limited to a tiny point towards the bottom of the diagram.

The action of taking a picture can be thought of as the combined effect of capturing the light from every single real world point visible from our camera position. Figure 3 shows this situation and demonstrates the (inverted) image captured by a pinhole camera.

Very quickly we can see a link between the dimensions of our pinhole camera box and the extent of the scene captured in our image. Figure 4a shows what happens when we build a longer box; our field of view (FOV) becomes narrow and only elements of the scene existing within a relatively thin cone are blown up onto our film plane. Figure 4b shows the effect of using a short box; our FOV becomes large and we capture light from a wider area.

Using some simple trigonometry, we can precisely define the field of view for any given combination of box length (which we will henceforth call focal length) and film plane size. Figure 5 demonstrates these calculations. The details are not important, but what is worth noting is that FOV is simply a function of focal length and film plane dimensions. This will be crucially important when we look at how changing lens changes the portion of the scene we record in our image. It will also explain why the same lens fitted to cameras with different sensor sizes will appear to behave differently (something camera manufacturers explain away with a ‘crop factor’).

In the next post, I’d like to extend the pinhole we’ve looked at in these examples into an idealized lens so that we can explore focus, aperture and exposure…

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)